Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation

Part 3: Every Neighborhood Needs Affordable Housing

In Chicago, the Affordable Requirements Ordinance (ARO) is a form of inclusionary zoning. The ARO aims to leverage market-rate developments to provide long term affordable housing units. Initially, in 2003, it applied to developments larger than ten units that received land or funding from the city. Consequently, affordable housing should make up 10% of the significant new developments over the next 30 years.

Every multifamily building we have built in our 20 years has had a client who has committed to exceeding the affordability requirements of the ARO, so here’s our Oakwood Shores Terrace Apartments, which are 75% affordable.

Expansion to Include All Zoning Changes

It was expanded in 2007 to include any planned development or any building that received a zoning change. These qualifications exist because the city is not legally allowed to require affordable housing in zoning. These requirements are permitted if the developer is receiving something from the city in exchange. These items the developer is receiving can be in the form of land, money, or zoning allowances. This policy constraint inadvertently encourages aldermen, alderwomen, and community groups to downzone areas, which keeps property zoned at densities below the historical development patterns of a neighborhood. Since zoning for the highest and best use of valuable land near amenities would not trigger the ARO, the community would not receive the 10% affordable unit set aside. This scenario is ironically most detrimental in wards that are experiencing gentrification. Since studies show displacement is most reduced by building affordable housing in tandem with new supply.

Loopholes Undermine the ARO and Exacerbate Economic Segregation

Initially, developers could pay a fee of $100,000 per unit in lieu of not providing the required affordable units. This led to projects in the most expensive parts of town just paying the “in lieu” fee. This both increased the cost of new multifamily housing, to the tune of $10,000 or more per unit. Without providing any new affordable housing in the neighborhoods lack it. Although it created a windfall for the city’s Affordable Housing Opportunity Fund. Which provides rental subsidies to low income Chicagoans.

However, the “in lieu” payment was not commensurate to providing 30 years worth of affordable housing in any neighborhood. Since $100,000 over 30 years would only be able to subsidize rent to the tune of $278 per month. As a result, the subsidies were primarily used to subsidize housing costs in more impoverished neighborhoods, further concentrating poverty — virtually the opposite of the stated goals of the program.

A First Attempt at Introducing Equity to the ARO

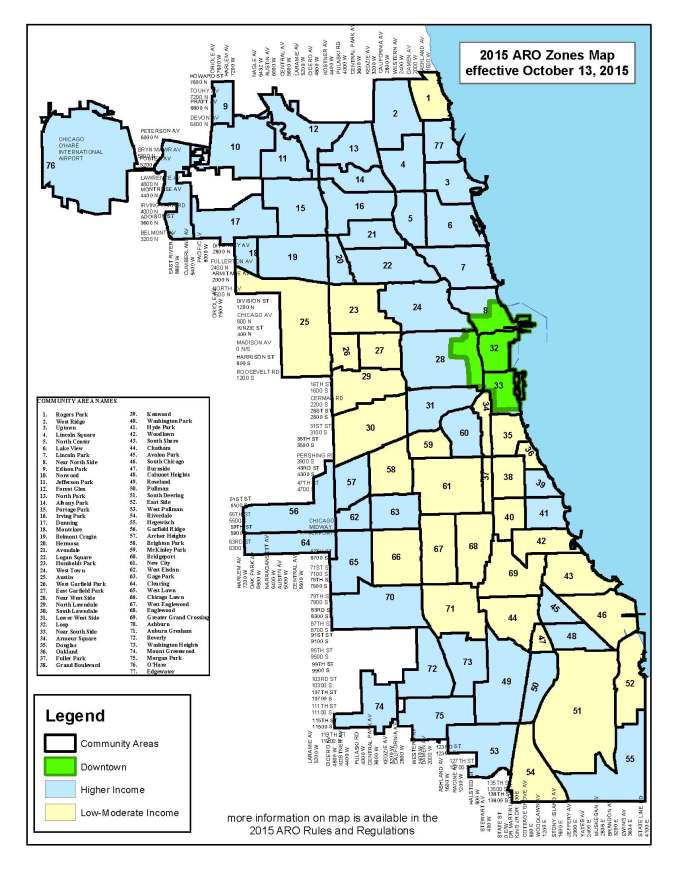

In response, Aldermen Walter Burnett (27th) & Proco “Joe” Moreno (1st) co-sponsored an expansion of the ARO in 2015. Their proposal increased “in lieu” fees in high-income areas downtown and for-sale developments like condos. The percentage of required affordable units was also increased to 20% if the city provided any financial assistance.

The ARO zone map courtesy of the City of Chicago website.

Additionally, 25% of the ARO units in a project were required to be built on site & could not be bought out via “in lieu” fees. The remaining units could be built off site as long as they were built within two miles of the development. Fees in low-moderate income community areas were cut in half, and were further reduced if CHA partnered with developers. Lastly, any Transit Oriented Development that provided 50% or more of the required ARO units on site would be eligible for an increased floor area ratio (aka additional rentable square footage).

Tailoring Affordable Requirements to Meet Neighborhood Needs

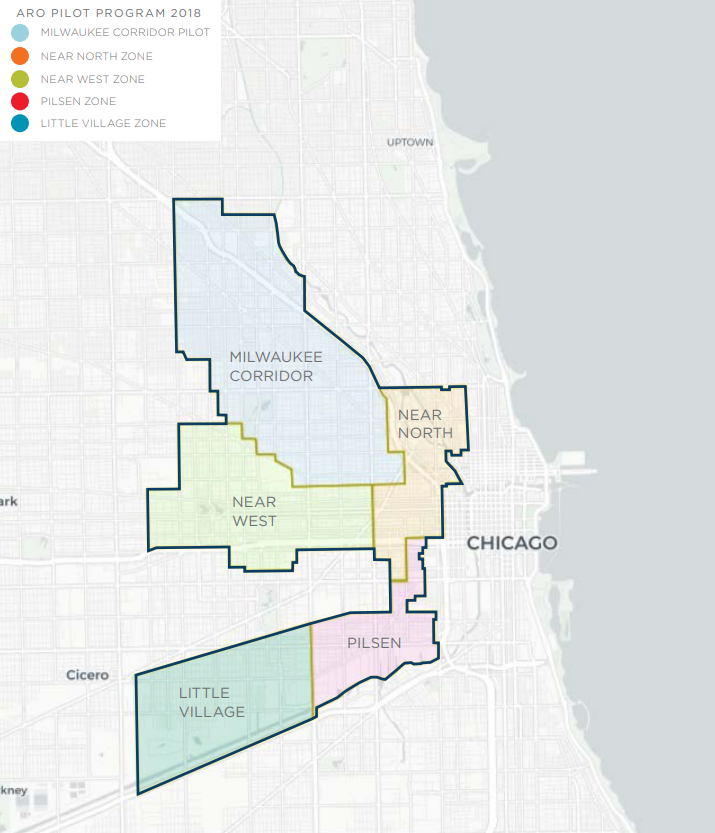

In 2017 three new ARO Pilot Programs were initiated that generally covered the areas represented by the aldermen who had sponsored the 2015 ARO expansion. The Near North/Near West Pilot areas are very similar to the boundaries of Walter Burnett’s 27th Ward. Its specific rules were developed to address issues in the ward. From a surge in development on the east to a lack of investment in new housing in the west.

Similarly, the Milwaukee Corridor Pilot covers the entirety of what had been Alderman Moreno’s 1st Ward. It also includes parts of Aldermens Ramirez-Rosa & Maldonado’s wards, the 26th and 35th Wards. Both aldermen campaigned on issues of affordable housing in their most recent elections. This Pilot Area basically eliminated the “in lieu” fees entirely, since most of aldermen representing this area don’t approve zoning changes for projects without the required affordable housing.

The ARO Pilot Areas map courtesy of a study by the Home Builders Association of Greater Chicago.

In 2018, two additional ARO Pilot Areas were created for Pilsen and Little Village in tandem with a comprehensive plan. Which was being developed for both community areas in regards to many issues, including historic preservation, the Paseo Trail, and Planned Manufacturing Districts.

What Else Can Be Done?

All of these changes have led to more affordable units than otherwise would have been built as part of large scale housing projects in gentrifying areas. However, there is still debate as to whether these policies have stifled the supply of new housing. Let alone whether that reduction in supply led to more existing affordable housing to be converted into luxury units.

The policies seem to work in high demand neighborhoods. Still, they have correlated with reduced construction in outer areas. Especially in terms of additional multi-unit housing in communities that were defined as low-moderate income and had suffered from decades of disinvestment. This scenario has set up an uneven form of redevelopment with very little middle ground. Either expensive single-family homes, or large-scale luxury developments that can afford to put aside affordable units. Even then, these large projects end up being opposed by neighbors living in single-family homes. This situation can result in new development being out of reach of existing neighborhood residents who are not already homeowners, which can lead to demographic change.

The residential component of our Englewood Arts + Crafts District Master Plan.

We know that the current ARO policy is leveraging affordable housing in places where Chicago is losing affordable housing due to market pressures. Now it needs to be balanced with zoning incentives for investment in neighborhoods that developers are currently avoiding. Luckily changes in City Hall are presenting a prime opportunity to reinvent policies so that they not only regulate development but simultaneously incentivize it. If you are interested in guiding this policy evolution, you should volunteer for the Chicago Department of Housing’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance Taskforce. We’ve already seen positive movement in the Qualified Allocation Plan, the draft rules for the Master Planned Development designation, and the Invest South West initiative. We’re excited to see how the reinvention of the ARO can reform how we provide affordable housing across the city.

Part Three of Four

This post is the third of four total posts in Nia’s Leadership blog. In the next final post, I will discuss the Transit-Oriented Development Ordinance.

About Author

Jacob Peters

Urban Designer / Project Designer

Jacob is a designer of urban and architectural projects at Nia. Jacob grew up and has lived most of his life in the City of Chicago. His training in architecture, his training in urban design, and his passion for improving cities combined with intimate knowledge of the City of Chicago makes him extremely insightful.

Related Posts

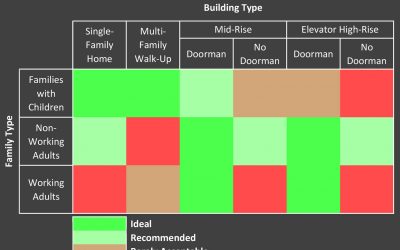

Ideal Architectural Housing Types for Different Lifestyles

Ideal Architectural Housing Types for Different Housing Families A look at Oscar Newman's suggestions for which building types are ideal for each individual and family size or lifestyle.Oscar Newman was an architect and a city planner who extensively studied public...

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 4: Leveraging our Transit Assets to Grow Communities

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 4: Leveraging our Transit Assets to Grow CommunitiesThe Transit-Oriented Development Ordinance (TOD) is another policy that was written with altruistic intents. It aimed to improve the affordability and...

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 2: Why Isn’t Every Chicago Street a Pedestrian Street?

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 2: Why Isn't Every Street a Pedestrian Street?In most of the world, the term "pedestrian street" means a street where cars are not allowed. Cafes sprawl across a brick-paved promenade with maybe a...

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 1: Capital Follows Capital

Spurring Development through Equitable Policy Implementation Part 1: Capital Follows CapitalEarlier this year, the Urban Land Institute study titled "Neighborhood Disparities in Investment Flows in Chicago." Many headline-reading, hot-take providers misinterpreted the...

Contact Us

Address

Chicago, IL 60607

Thank you for sharing such a blog!

Best regards,

Lunding Hessellund

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Thanks, However I am experiencing problems with your

RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I cannot join it. Is there anyone else getting identical

RSS issues? Anyone who knows the answer will you kindly respond?

Thanx!!